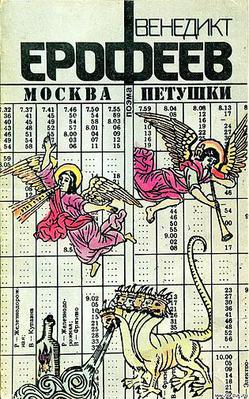

Yes, and no. The play opens up splendously with Clayton Jevne coming out to talk about wandering the streets of Moscow unable to see the Kremlin. If you've never been to the city, by the way, it's quite the feat: only about 3 different subway stations drop you off near Red Square, and if like our protagonist you've ever wandered along the Moskva you really have to try very very hard not to find yourself at its imposing walls wondering how many cameras are watching you at this very moment but still probably fewer than if you were in Westminister. Vanya, however, has managed to do this. He's an employed alcoholic in the Soviet Union of the 70s, the kind of chilling social structure that the infamous 99% would find themselves committing emo-suicide if they lived in even as they demand identical government policies. He was fired from his State job for publishing tongue-in-cheek individualist reports (about staff alcohol consumption), and finds himself aimless wandering around with a suitcase full of hooch and a dream in his heart.

Vanya, you see, is in love. His love, and their love-child, live in Petushki where Vanya visits every Friday. On this particular day, Vanya is very excited to see his lover for the 13th Friday. Thirteen Fridays barely put Vanya's girlfriend into the second trimester, which instantly makes you think either this drunken fool is paying penance for a one-night stand a couple years earlier, or maybe these Ruskies aren't quite as good at math as they're cracked up to be. Vanya tells of his troubles in the morning, those horrible hours before bars open but after the sun has voskres, where the mere suggestion that he might like a drink gets him thrown violently out of cafes. Fortunately for Jevne, his character has a preference for clear liquors that can be replaced on stage by water: the actor is quite clearly not Russian but does put a slight hint of slavic into his slurred accent. But while Vanya cannot ever see the Kremlin (so wait, he never went to St. Basil's either?) he is very adept at finding his way to Kursk train station, where he begins his happy journey to Petushki and his love(s?). It's also where we the audience start to lose the play.

Vanya tells tales of his refusal to pay the conductor, and instead tricking his comrade into forgetting to ask for a ticket by telling tales of world history. He references a lot of classic mythological literature, a bit of Russian but certainly not entirely, and delights the conductor in a manner that we the audience quickly tire of. By the time he starts getting into Petushki district, unfortunately, you've been having too much difficulty following along and the mind starts to wander. Somehow Vanya misses his stop, and/or gets off and then back on a southbound train to Moscow. Fortunately this doesn't mark the halfway point, and once he's back in Moscow the play gets enough of its energy back to take you to the final confrontation with agents of the state (in the book, thugs) who somehow seize upon poor Vanya and chase him to -- the Kremlin -- where he meets his ever-so-Russian demise.

This is a great play while Vanya tells of his drunken memories of criss-crossing the streets and recalling the drinks he must have had or wishes to have, and his faithful reproduction of the book's opening chapters is impressive. Unfortunately Vanya also goes through "History of the World, Part I" and the Soviets wouldn't accept Jews in Space.

Final word: Moscow Stations is a beautifully tragic tale of woe, a classic fringe theatre play that you probably should see, and a great portrayal of alcoholism. But don't have a drink before you go in, or you'll fall asleep long before Petushki.